The Glass House

Tucked away in a quiet street in a well-off residential area up the hill just off the Brno town centre, you might easily pass by her minimalist front facade without noticing.

Villa Tugendhat. The glass house.

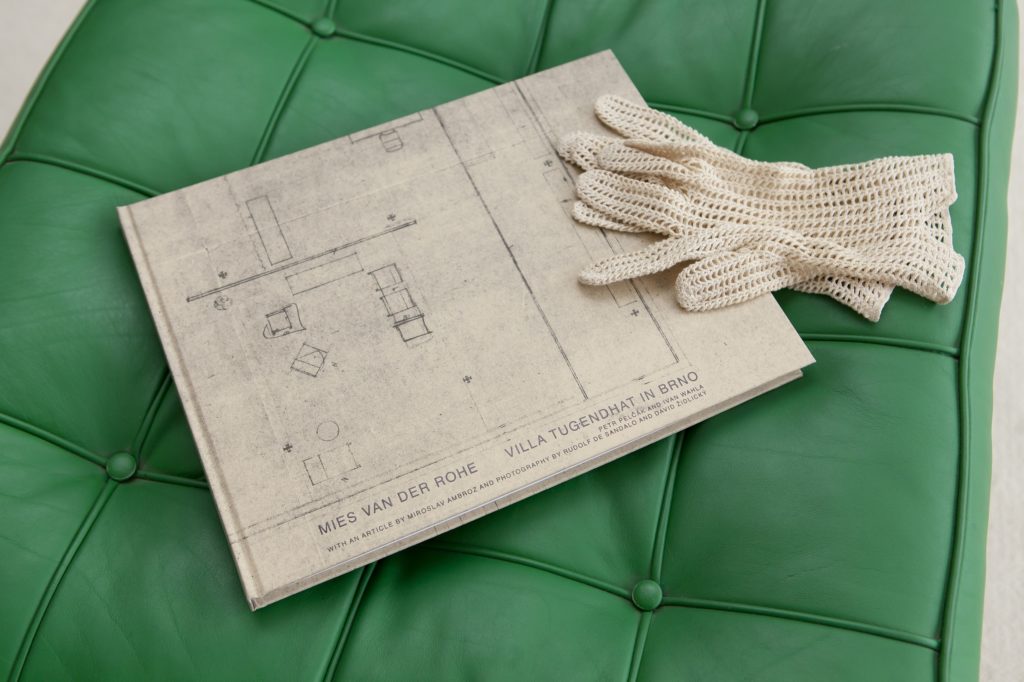

UNESCO protected masterpiece of modernist and functionalist architecture, built by Ludwig Mies van Der Rohe in the years 1929-1930 for the newly married couple Grete and Fritz Tugendhat.

Both Grete and Fritz came from affluent families of the so called textile barons, who prospered from then thriving textile manufacturing (in the 19th century, Brno used to be dubbed the Moravian Manchester). When they decided to build a family residence on the vast yet slopy plot Grete’s father gave them as a wedding gift, they commissioned the design to an architect whose work they were impressed with – Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. They granted him a limitless budget!

Our first visit to Villa Tugendhat was in 2010, and at that time, our focus was on its breakthrough architecture and design we’d read so much about. Despite dilapidation and damage caused by decades of neglect, and with missing inventory, we were captured by her timelessness, splendour and genius loci.

Villa Tugendhat is the model representation of Mies van der Rohe‘s ‚Less Is More‘ design principle, with its light and airy open plan, sparse use of furniture, specifically designed for the house, and no decorative objects whatsoever. Yet the space does not feel austere, due to the use of luxurious natural materials, such as yellow oxyx and exotic woods. The only piece of art chosen for the house was the ‚Torso‘ by Wilhelm Lehmbruck.

Perhaps the most iconic architectonic feature though, that also gave Villa Tugendhat its moniker – the glass house – is a glass wall on the facade overlooking the garden and offering panoramic views of the Brno skyline. Its massive glass panels slide into the basement, thus connecting the interior with the garden which was designed as an integral part of the living space.

To truly appreciate how radical and bold this architectonic concept must have been at that time, it’s worth visiting Villa Löw-Beer, within the walking distance, situated at the lower end of the very same plot and garden; it’s the house where Grete’s parents lived.

Quite unexpectedly, our first visit turned to be quite an emotional experience, too. We left moved and saddened. By the state this building was in. By the cataclysmic events that changed the lives of her commissioners forever.

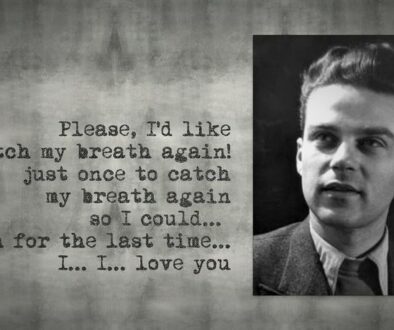

The young Tugendhat family had mere eight years to enjoy their house. Being Jewish, they were forced to flee from Czechoslovakia in 1938, shortly before the country was torn apart as a result of the Munich Agreement, and occupied by the Nazis a year later. They never came back.

Villa Tugendhat has never been lived in again.

Instead, it became a poignant reflexion of the country’s historic turmoils: seized by the Gestapo in 1939, it served as a Messerschmidt office during the WWII, only to be looted by the Soviet Red Army after the liberation of Brno in 1945 (can you believe the Russians used its mahogany library as a horse stable?!). In the 1950s the villa became property of the national administration and served as a dance school and later as a rehabilitation and physio exercise centre. In the 1960s, the plans finally began for her restoration and use for cultural events. Yet another occupation, that of 1968 by the Soviet army, interrupted these plans and it was not until 1980s, after Villa Tugendhat became property of the Brno Municipality Council when plans for its restoration began anew. A major restoration and reconstruction project took place between 2010-2012.

Our second visit in August 2017 was much more light-hearted. At that time Villa Tugendhat was already brought back to her nearly original glory. It opened to the public, and became a distinct cultural and social venue. On a hot summer’s day, with the huge glass wall hid in the floor, the refreshingly breezy view from under the marquee felt almost like we were on a captains bridge.

Only the statuette was missing. Returned to the Tugendhat family as a compensation to the victims of holocaust, only to be sold in an auction in London few months later. We will never see her again (although this is not entirely true; the original artwork has been replaced by rather a dissappointing copy).

Over the years and our multiple stays to Brno, our connection to the Villa Tugendhat became very personal.

So much so that for the third time around, we treated ourselves to a very special and private time in this iconic house. Our wedding day. It felt like for one single day in January 2018, Villa Tugendhat belonged to us (we even got the key!). Perhaps we experienced what it must have felt back then, when private social gatherings of family and friends frequently took place there.